Why Cage Your Inner Editor?

I am constantly surprised by professionals who are tentative about editing someone else’s work, particularly when it’s their job to make the communication as effective as possible. For a long time, I attributed it entirely to group dynamics, the idea being that no one wants to step on anyone’s toes.

But recently I’ve come to think there’s a much simpler explanation. Most people have never been shown how to edit someone else’s work. I mean, physically walked through the process. Most of what passes for writing education is the dissemination of rules, principles and best practices. But there’s a constant gap between knowing what to do and knowing how to do it.

It’s why reading books about editing won’t make you a good editor. Until you perform editing tasks, you only have knowledge and not experience. I started thinking about where I learned to edit, who modeled it for me and if I could pass that knowledge along? I had several formative experiences, including:

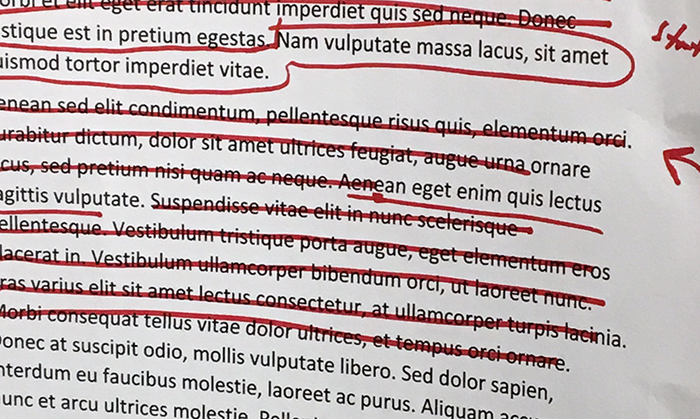

- One of my early composition teachers wrote extensive feedback on every assignment. She would cross out entire sections of an essay, correct grammatical errors, ask questions in the margins, write long explanations for her edits. It was a peek into the mind at work during the editing process.

- Writing and workshopping poetry, I learned not to take criticism personally, to hear other perspectives, concentrate on concision, and weigh the meaning and context of every word. I also learned that the writing is never done. You can always make more changes, so at some point you just have to cut it off.

- Early in my career, I had mentorship from great newspaper and publishing professionals. Editing and rewriting are (or used to be) taken for granted in newsrooms. You might argue over an edit, but you didn’t expect not to be edited.

- Working directly on layouts in desktop publishing programs, I confronted the process of editing in the most visceral way. One of my tasks as a young editor was to cut the overflow copy after it was laid out by the designer. When you see exactly how much space you have and know exactly how much has to be cut, you start whacking away.

The last item strikes me as one of the most important. The actual physicality of deleting whole chunks of text and then rewriting other chunks, making decisions about what was most important and what could go – that is an experience most people don’t get.

A Simple, Surprisingly Powerful Editing Exercise

Set aside the politics around editing your co-workers’ writing for a moment. What stops you from rewriting a 1,000-word memo when it would be better off as a 250-word memo? If my theory is correct, that most people have never had the physical sensation of editing for length and organization, then what can we do about it?

Toward that end, I crafted an exercise several years ago to use in my corporate training workshops. It starts with a rambling 800-word ‘letter’ about my travels to another country. I wrote it in a sitting, without stopping, so it would be deliberately associative.

The task for workshop participants is to reduce the letter from its original length to 1) 400 words, 2) 50 words and 3) 140 characters.

Set up this way, participants have no choice but to start crossing out huge chunks of text, including sections that might have been well-written and filled with interesting details.

It also forces participants to make choices about what is most important in the letter. They have to decide on an assumed audience.

In discussions afterward, we compare the results and talk about the choices they made. But when participants also talk about the experience they had, how good it feels to take control of the text, to delete and rearrange with confidence – then I know it’s a success. MW